Remembering Gyo Obata

2022-03-11 • Liam Otten

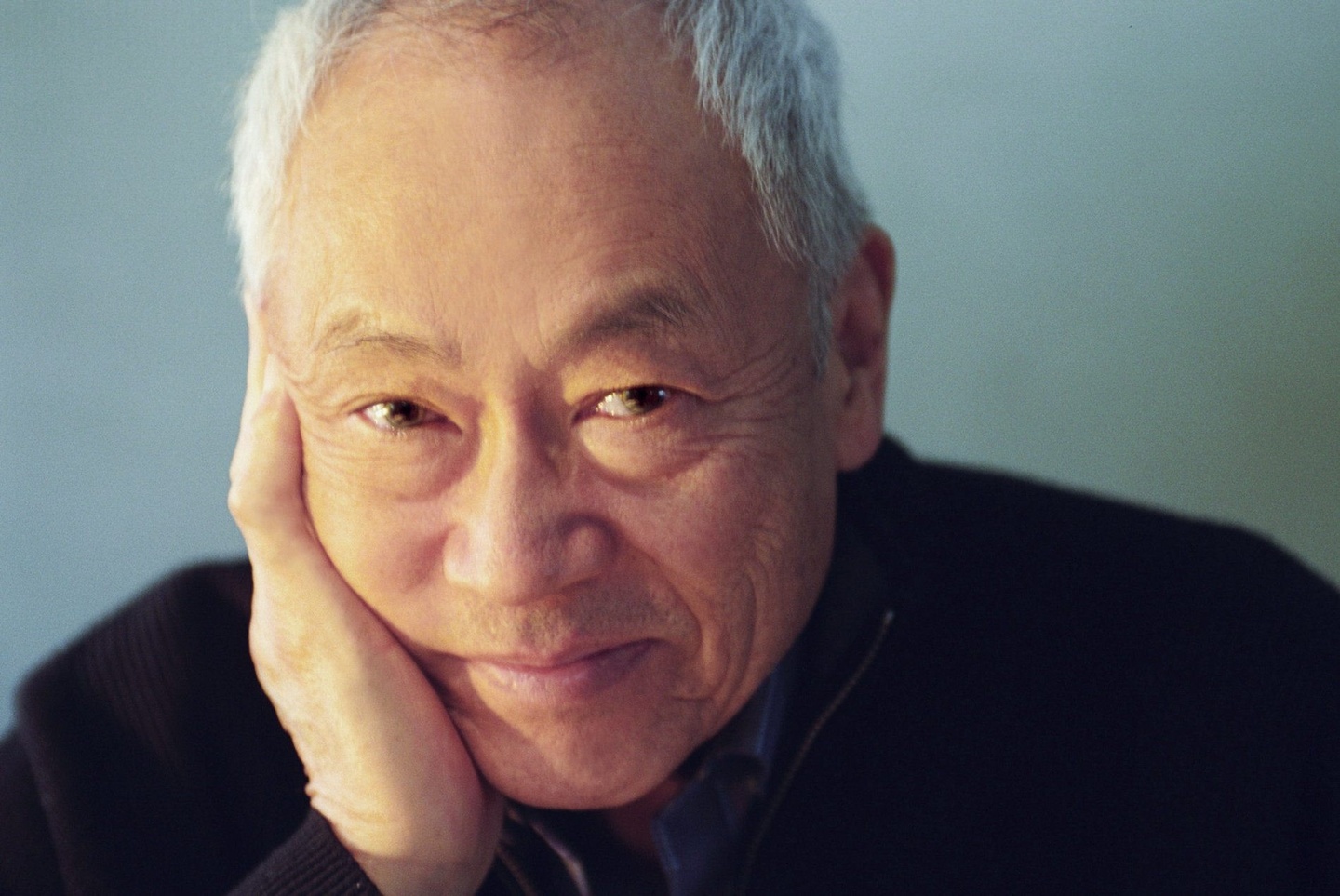

Gyo Obata.

Gyo Obata, one of the world’s most celebrated architects and a cofounder of Hellmuth, Obata & Kassabaum (HOK), died March 8, 2022, in St. Louis. He was 99.

In a career stretching more than seven decades, Obata designed scores of structures, ranging from the groundbreaking Priory Chapel at Saint Louis Abbey and the iconic James S. McDonnell Planetarium at the Saint Louis Science Center to the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., the Japanese American National Museum Pavilion in Los Angeles, and King Saud University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

“Gyo Obata was an extraordinary designer, a visionary leader, and a deeply thoughtful man,” said Carmon Colangelo, the Ralph J. Nagel Dean of the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis, Obata’s alma mater.

“His bold forms, collaborative approach, and sensitivity to the natural environment have helped to shape the course of contemporary architecture,” Colangelo added. “He was a towering talent who will be sorely missed.”

A remembrance service will be held at 1p Saturday, May 14 at The Abbey Church at Saint Louis Priory School, 500 S. Mason Rd., Creve Coeur, MO 63141.

Coming to St. Louis

Born in San Francisco in 1923, Obata was the son of painter Chiura Obata and floral designer and ikebana artist Haruko Obata. In 1942, Gyo was a freshman at the University of California, Berkeley—where his father taught—when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order #9066. This would force approximately 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, two-thirds of them American-born, from their homes and into internment camps.

Two months later, the Obata family was ordered to the Tanofran detention center in San Bruno, California. (Their final destination would be a camp in Topaz, Utah.) But as they prepared to leave, Gyo received word that he’d been admitted to WashU’s School of Architecture. He boarded a train for St. Louis that evening.

“If you got an acceptance from a university away from the West Coast, then you could leave California,” Obata explained to Washington University Magazine in 2017. “I was able to leave the night before my family … was moved into camp.”

At WashU, Obata’s classmates would include celebrated architects Richard Henmi and George Matsumoto, and sociologist Setsuko Matsunaga Nishi. In 1945, he earned his bachelor of architecture degree and was awarded a scholarship to attend graduate school at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan. There, he studied with revered Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen—father of Gateway Arch designer Eero Saarinen—and earned a master’s in architecture and urban design.

Left: Gyo Obata on the Washington University campus in 1942.

Obata graduated from Cranbrook in 1946 and soon was drafted into the U.S. Army, which sent him to design bridges in Adak, Alaska. After discharge, in 1947, he worked with Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill (SOM) in Chicago before joining Hellmuth, Yamasaki, and Leinweber in Detroit in 1951. Working with Minoru Yamasaki (who later designed the World Trade Center in New York City), Obata helped to establish the low-slung arches and sleek, aerodynamic lines of what would become St. Louis Lambert International Airport—a building widely credited with reshaping the visual vocabulary of modern airport terminals.

A Broad Practice

In 1955, Obata teamed up with fellow WashU alumni George Hellmuth and George Kassabaum to found HOK.

“It was tiny,” Obata said, in 2017, of the firm’s original St. Louis office, “the three of us and half a dozen other draftsmen. But we wanted to work on many different types of projects. We wanted a practice that was very broad.”

Today HOK employs more than 1,600 people in 24 offices on three continents, making it one of the world’s largest architectural practices. Initially focusing on the area of education, HOK quickly expanded to include corporate facilities, airports, hotels, research and educational facilities, places of worship, sports venues, parks, hospitals, criminal justice facilities, shopping centers, and museums.

Notable projects include Baltimore’s Camden Yards; the U.S. Olympic Fieldhouse in Lake Placid, New York; the Bristol Myers Squibb Headquarters in Princeton, New Jersey; Southern Illinois University Edwardsville (SIUE); the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library in Springfield; and the Dallas-Fort Worth Airport—a site larger than the island of Manhattan.

In St. Louis, Obata’s many designs include the Living World at the Saint Louis Zoo; the Missouri History Museum Emerson Center; the Thomas F. Eagleton U.S. Courthouse; the Washington University School of Medicine Farrell Learning and Teaching Center; and Centene Plaza, among many others.

Levi’s Plaza, San Francisco. Photo: Peter Aaron, courtesy of HOK.

The Quality of Life

“My core philosophy as an architect and as a person stems from my earliest lessons as a boy,” Obata told author Marlene Ann Birkman in Gyo Obata: Architect | Clients | Reflections (2010). “Listen very carefully and understand what people want, work hard, and find the best ways to enhance the quality of life around you.”

Obata retired from HOK in 2012 but continued to serve as a design consultant until 2018. A fellow of the American Institute of Architects, he received the Gold Honor Award from the St. Louis Chapter of the AIA in 2002. The Japanese American National Museum honored him with a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2004.

At WashU, Obata received an honorary doctorate in fine arts in 1990 as well as the Dean’s Medal—which recognizes individuals whose extraordinary contributions have elevated the fields of art, architecture and design—from the Sam Fox School in 2008. In 2010, the Sam Fox School established the Gyo Obata Scholarship in his honor.

Obata is survived by his wife, Mary Judge; by his children Kiku Obata, Nori Obata (Esteban Prieto), and Gen Obata (Rebecca Stith), and their mother, Majel Obata; and by his son, Max Obata (fiancée, Emma Fisher), as well as six grandchildren and eight great grandchildren. His wife, Courtney Bean Obata, mother of Max Obata, preceded Mr. Obata in death.

Memorial donations can be made to the Sam Fox School’s Gyo Obata Scholarship, or to the Saint Louis Art Museum, Missouri Botanical Garden, Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra, Opera Theatre of Saint Louis and Planned Parenthood.

Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, Springfield, Illinois. Photo: Timothy Hursley, courtesy of HOK.