The ABCs of Art and Politics

2020-08-24 • Liam Otten

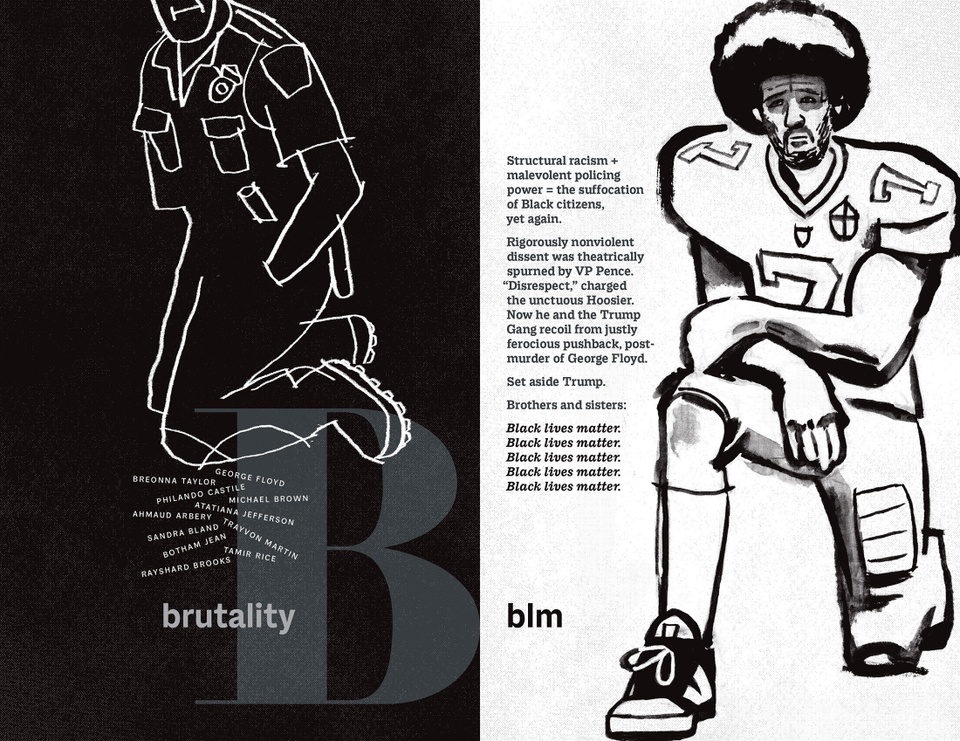

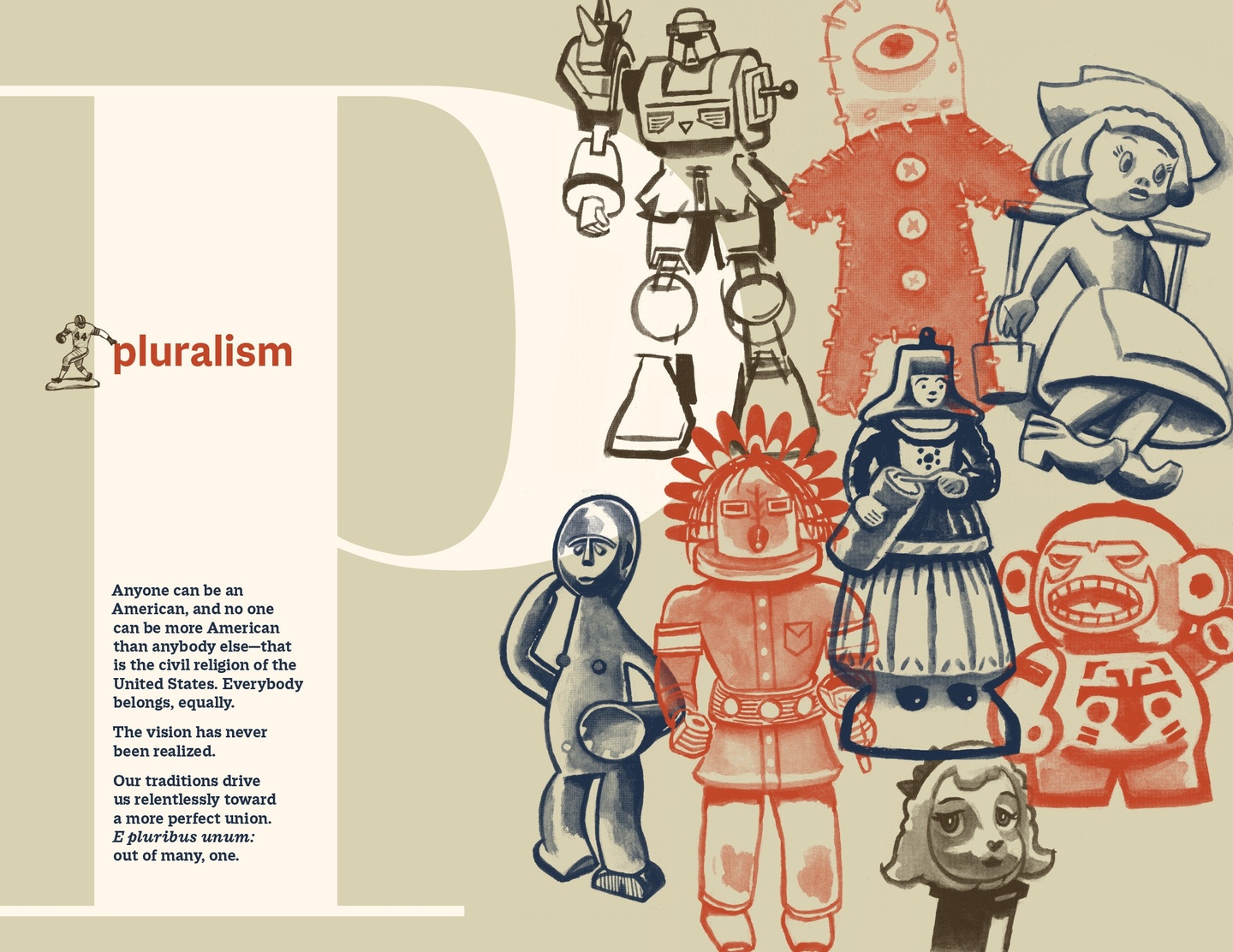

A page from D.B. Dowd’s A is for Autocrat (Spartan Holiday Books, 2020).

How do you illustrate pluralism?

For D.B. Dowd, professor of art in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis, the question was quite literal. In his new book, A is for Autocrat, the nationally known artist and prolific author, drawing in part on James Madison’s Federalist No. 10, sought to articulate a positive position for diversity. But he also wanted to avoid any hint of stereotype or pat characterization.

“It’s the ‘Golden Rule’ problem,” Dowd quips, pointing to the 1961 painting by Norman Rockwell (whom Dowd otherwise largely admires). Though well-intentioned, the piece consists of “earnest-looking people from vastly different backgrounds, appropriately costumed, standing around.

“I needed to capture some of that spirit, but with much more attitude.”

There is no shortage of attitude in Autocrat, which Dowd’s publishing company, Spartan Holiday Books, will release Aug. 28. Subtitled A Trumpian Alphabet, Illustrated, it draws on Dowd’s deep knowledge of illustration and political cartooning to mimic the look and feel of a mid-century children’s alphabet book.

In this Q&A, Dowd, who also founded and directs the university’s D.B. Dowd Modern Graphic History Library, discusses Autocrat, his artistic process, and what happens when political discourse grows too outlandish for satire.

What drew you to the “alphabet book” format?

In 2018, while spending Thanksgiving in Virginia with family, I came across a brief guide to character education for children in a Lynchburg antique mall. It had been put out by the Grolier Society, publishers of The Book of Knowledge, an encyclopedia for kids.

On the last several pages of that yellowed booklet, the editors provide something called “The Children’s Morality Code,” a concise set of guidelines for being a good person. “The Law of Truth,” for example, covers how a person should respect, guard and never hoard the truth. It felt like an indictment across time. I plunked down the $7 and brought it back to my studio.

By choosing an ABC format, I let myself be challenged by the Grolier’s guide to communicate as if to children: To use plain language in short segments, straightforward typesetting and clear illustration to address the moral catastrophe we are living through.

While Autocrat isn’t for an audience of children, it uses strategies that appeal to kids. A friend who saw an early version of the book wrote, “It was the first time in a long time that it seemed possible to channel my rage constructively, from A to Z.” That captures what I’m hoping to achieve. Be mad, but don’t despair. Clarity can be a motivator.

You grew up in a Republican household. Your father, David Dowd, was a U.S. district judge, appointed by President Ronald Reagan. What would he have thought about this book?

I’ve thought a lot about my dad while working on this project. He was powerfully committed to the law, and the folks who worked with him—including defense lawyers and prosecutors—regarded him as a deeply fair judge. Four summers ago, Dad was dying of leukemia in Florida as Trump captured the Republican nomination. I was able to be with him throughout his last weeks, and among the things we did together was to watch the two political conventions.

He didn’t make it to November, but he was planning to vote for Hillary Clinton. He found Trump’s dismissive view of public service obnoxious and saw him as a threat to an independent judiciary.

I think he would enjoy the book. He took citizenship very seriously.

“Sam the Dog,” your satirical comic strip, ran in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch from 1997-99. But in recent years, you’ve turned away from cartooning and focused more on reportage—even mentoring a group of student artists who covered the 2016 presidential debate at WashU. What’s driven that shift?

“Sam the Dog” told a story of a racially balkanized river town and relied on exaggerated characters to drive the narrative. But, starting around 2007, I stopped making cartoons, partly because the increasingly exaggerated quality of public discourse had made satire less fun. At that point, I didn’t want to comment anymore, I just wanted to describe. And, believe it or not, that journalistic impulse drove “Autocrat,” too.

I had to give form to what I was seeing and reading. The Trump administration and its characters are so outlandish that simple description feels like commentary. So, in spots, I have come back to cartooning. On the “O is for Odious” page, I drew the attorney general as a toad and the Senate majority leader as a snake. But I’m not trying to be funny. I’m trying to be clear.

What other sources or design traditions influenced you?

I drew on all sorts of visual culture. For example, Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump figure prominently in “H is for Hubris.” I wanted to capture their insinuation into settings and professional contexts far beyond their qualifications. In the 1940s and ’50s, Jack and Jill magazine ran a paper doll feature every month. I dug into my research library and found half a dozen issues for reference. My version highlights the ways Jared and Ivanka have “played” government.

To illustrate “L is for Lackey,” I used macaque monkeys to show cringing Senate support. My reference was a leaf from an 1896 German encyclopedia I picked up years ago at a library deaccession sale. “K is for Knowledge” draws on mid-century science books for young people. And so on. I engage with popular sources like these in a sort of homage. They’re rich with meaning. Unassuming images can do a lot of work when tethered to the right concept.

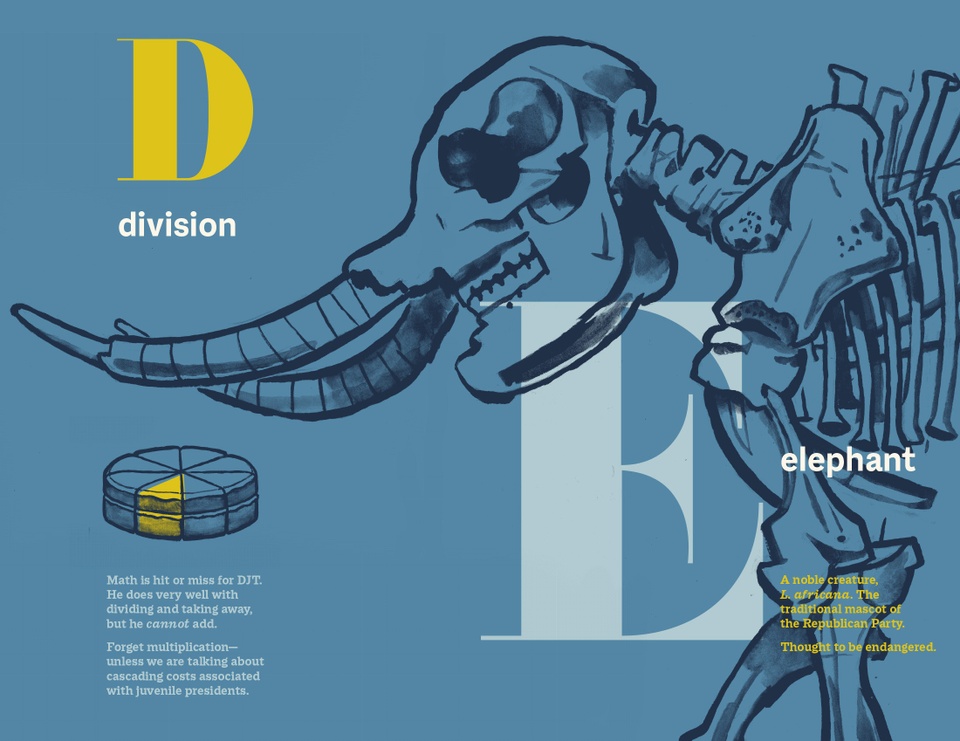

At the University of Nebraska, where I went to graduate school, there’s a natural history museum filled with skeletons of mastodons and other elephant precursors. A year ago, on a research trip, I made a pencil drawing of a reconstructed mastodon skeleton. Several ABC books from the 1920s and ’30s used the E slot for “Elephant.” And I think the Republicans have so disgraced themselves that the party deserves to die—making way for the new center-right party, one that would accept science, climate change and reasonable immigration policies. Those ideas led me back to that sketchbook. I inked the pencil of the mastodon skeleton and called it an elephant.